Copyright [year?], University of California Press. All rights reserved.

H. St. P. P. Brandon, Detective Head Constable, to Boksburg District Commandant, South African Police

BOKSBURG,[1] 9/2/1920

Sir:

I beg to report for your information that at 2 P.M. Sunday the 8th instant, I attended the Native Congress Meeting[2] at the Blue Sky.[3]

Native Daniel Tlhdaele, the local Chairman[,] opened the meeting by saying that the object was to get better wages for the natives.

Native Ngoja of Johannesburg then got up. He said that he had come there to strengthen the purpose of the Congress, that he wanted to make it clear to them that they, as a black race, must know that the white people were thieves and devils. The white people came to Africa and stole their country. The white people were devils of the worst kind and they all go to hell, they were full of devil's tricks, the Pass Law was one; the Pass Law must be thrown out. Africa was the black people's country. God gave it to them. The black people must use their eyes, their heads and their strength to get their country back. They must not be cowards. God did not want cowards. They must look to the gaols as their homes. The mine natives must also know that they are the producers of the wealth and they must get better pay. That in Natal and in Kimberley the natives refused work, they said they were hungry; they were given more money. At Pietermaritzburg[4] they were getting £1–18/– per week; at Kimberley[5] £2 per week. There must be unity among the black people. The town lights can be put out, one white stick cannot break ten black sticks[.] (I have since learned that the ordinary Native interpretation of this is:—The lights are the white people, the sticks 10 blacks to one white one; to put out means to kill, I merely mention this because it was put that way to me[.]) The speaker went on to say that Natives must not cont[r]act themselves to white people, they must free themselves. God gave them strength, they must make the white people work for it and pay for it. He said Native Duba[6] in Natal said the Pass Law was a good thing. Duba is a fool, he is mad.

There was then a collection to pay the Congress expenses.

Native Ngoja then renewed his attack on the white people, in same strain. He said [David] Lloyd George said he did not know the black people were so badly treated in Africa,[7] but even Lloyd George was a white man and cannot be trusted, when[e]ver the word white man was used he was called a thief or satan. He further said that the Congress members who were sent to Europe are on their way to America[8] and that they will get satisfaction there. America said they will free all natives, and they will help. That America had a black fleet and it is coming. (this is interpreted as the time to start trouble).

At this stage a rain storm came on and the meeting f[i]nished.

I was the only white person there, the 300 or 350 natives cheered the speaker every time he blackguarded the white race. I was pointed at all the time. There was no one there from the Native Affairs Department.[9]

[H. St. P. P. Brandon] Detective Head Constable

SAGA, 3/527/17, pt. 6. TL, carbon copy.

[1] Boksburg, a lakeside town on the Witwatersrand a few miles east of Johannesburg, was founded in 1903. Its 1921 population of 37,979 included 24,318 Africans and 12,416 Europeans (Official Year Book of the Union, no. 7, 1924 [Pretoria: GPO, 1925], p. 125; ESA).

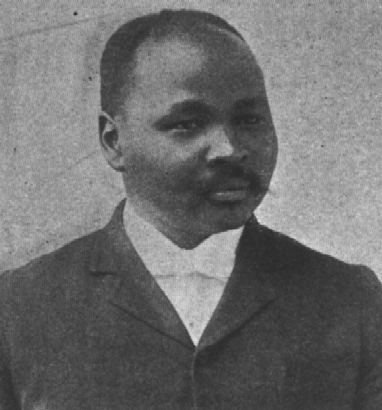

John L. Dube

[2] The South African Native National Congress (SANNC) was launched in Bloemfontein in January 1912, two years after the establishment of the Union of South Africa. Its formation was closely linked to black rejection of the Union constitution and the discriminatory legislation that immediately followed union. The leading figure in the formation of the SANNC was Pixley ka Izaka Seme, a young lawyer who had recently returned from studies overseas and who, together with Alfred Mangena, George Montsiao, and Richard Msimang (all of whom were also lawyers who had studied abroad), took the initiative in planning the organization's inaugural conference. John L. Dube became the first president, Solomon Plaatje, secretary, and Seme, treasurer. The SANNC's major aim was to unite Africans—in particular, small, locally based organizations such as its regional branch, the Transvaal Native Congress—into a single national movement. The SANNC was renamed the African National Congress (ANC) in 1923; it would become the most important black political organization in South Africa, a stature it still holds today (Edward Roux, Time Longer Than Rope: A History of the Black Man's Struggle for Freedom in South Africa, 2d ed. [Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964]; RANSA; FPC 1, 4; P. L. Wickins, The Industrial and Commercial Workers' Union of Africa [Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1978]; ESA).

[3] New Blue Sky was an early mine in Boksburg. The Cinderella Prison in Boksburg was also known as "Blue Sky" (ESA).

[4] Pietermaritzburg, the capital of Natal province, was named to honor two Afrikaner leaders, Piet Retief and Gert Maritz. The town's 1921 population was 36,023, of which 17,998 were European, 9,992 were African, and 6,944 were Indian (Official Year Book of the Union, no. 7, 1924 [Pretoria: GPO, 1925], p. 125; ESA).

[5] Kimberley, a city in northern South Africa, developed as a result of the discovery of diamonds in the nineteenth century, and remains a center of the diamond industry. In 1920 its population of nearly forty thousand was almost evenly divided between Europeans (18,288) and Africans, Indians, and those of mixed race (21,414) (Official Year Book of the Union, no. 7, 1924 [Pretoria: GPO, 1925], p. 125; William H. Worger, South Africa' s City of Diamonds: Mine Workers and Monopoly Capitalism in Kimberley, 1867 – 1895 [New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1987]).

[6] "Native Duba" was almost certainly John L. Dube.

[7] An account of the interview published in the December 1919 African Telegraph (London), and reprinted in the 17 January 1920 African Sentinel (London), provided the following description of British prime minister David Lloyd George's reaction to the SANNC deputation:

The Prime Minister, who received the deputation in a cordial manner, was visibly moved by the speeches, and listened attentively to the tale of woe which was revealed to his wondering eyes. In reply, the Prime Minister, whilst thanking the deputation for the able and effective manner in which they had stated their case, paid a warm tribute to the loyalty of the natives to the Empire, and pointed out the constitutional difficulty that lay in the path of the Imperial Government as regards interference with the internal acts of a Dominion Government, but, nevertheless promised to communicate with the Prime Minister of the South African Union with a view to ascertaining what could be done in the way of ameliorating the conditions complained of. The Prime Minister then shook hands with all the members of the deputation and retired. (African Telegraph [London], December 1919)

[8] Most of the members of the delegation returned to South Africa in 1919 and 1920. Solomon Plaatje, however, sailed for Canada in October 1920, spending nearly two years there and in the U.S. (Brian Willan, Sol Plaatje: South African Nationalist, 1876 – 1932 [Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1984], pp. 259–281).

[9] The Department of Native Affairs was established in 1910, with the formation of the Union of South Africa. The department, which took over the jurisdiction of similar departments that had existed in the four former colonies prior to the union, was administered by the governor-general, who held the additional title of minister of native affairs. Responsibilities of regional staff included administration of the Native Land Act of 1913, along with oversight of agricultural practice, health regulations, taxation, and education (W. K. Hancock, Smuts: The Fields of Force, 1919 – 1950 [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968], p. 111; SESA).

Recommended Citation:

The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers,

ed. Robert A. Hill

(Columbia, S.C.: Model Editions Partnership, 2000).

Electronic version based on

The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers,

ed. Robert A. Hill,

Volume 8,

(Berkeley: University of California Press, [year?]). On the Web at http://mep.blackmesatech.com/mep/ [Accessed 27 March 2025]